Nobel Lecture

7 December, 2012

(by Mo Yan, harshly criticized since his award. Res ipsa loquitur — the thing speaks for itself — and his speech here is beautifully written as it is profoundly moving. Res ipsa loquitur — the criticism of his detractors, no matter how right they feel they are politically, speaks criticism. Not art. )

Storytellers

Distinguished members of the Swedish Academy, Ladies and Gentlemen:

Through the mediums of television and the Internet, I imagine that everyone here has at least a nodding acquaintance with far-off Northeast Gaomi Township. You may have seen my ninety-year-old father, as well as my brothers, my sister, my wife and my daughter, even my granddaughter, now a year and four months old. But the person who is most on my mind at this moment, my mother, is someone you will never see. Many people have shared in the honor of winning this prize, everyone but her.

My mother was born in 1922 and died in 1994. We buried her in a peach orchard east of the village. Last year we were forced to move her grave farther away from the village in order to make room for a proposed rail line. When we dug up the grave, we saw that the coffin had rotted away and that her body had merged with the damp earth around it. So we dug up some of that soil, a symbolic act, and took it to the new gravesite. That was when I grasped the knowledge that my mother had become part of the earth, and that when I spoke to mother earth, I was really speaking to my mother.

I was my mother’s youngest child.

My earliest memory was of taking our only vacuum bottle to the public canteen for drinking water. Weakened by hunger, I dropped the bottle and broke it. Scared witless, I hid all that day in a haystack. Toward evening, I heard my mother calling my childhood name, so I crawled out of my hiding place, prepared to receive a beating or a scolding. But Mother didn’t hit me, didn’t even scold me. She just rubbed my head and heaved a sigh.

My most painful memory involved going out in the collective’s field with Mother to glean ears of wheat. The gleaners scattered when they spotted the watchman. But Mother, who had bound feet, could not run; she was caught and slapped so hard by the watchman, a hulk of a man, that she fell to the ground. The watchman confiscated the wheat we’d gleaned and walked off whistling. As she sat on the ground, her lip bleeding, Mother wore a look of hopelessness I’ll never forget. Years later, when I encountered the watchman, now a gray-haired old man, in the marketplace, Mother had to stop me from going up to avenge her.

“Son,” she said evenly, “the man who hit me and this man are not the same person.”

My clearest memory is of a Moon Festival day, at noontime, one of those rare occasions when we ate jiaozi at home, one bowl apiece. An aging beggar came to our door while we were at the table, and when I tried to send him away with half a bowlful of dried sweet potatoes, he reacted angrily: “I’m an old man,” he said. “You people are eating jiaozi, but want to feed me sweet potatoes. How heartless can you be?” I reacted just as angrily: “We’re lucky if we eat jiaozi a couple of times a year, one small bowlful apiece, barely enough to get a taste! You should be thankful we’re giving you sweet potatoes, and if you don’t want them, you can get the hell out of here!” After (dressing me down) reprimanding me, Mother dumped her half bowlful of jiaozi into the old man’s bowl.

My most remorseful memory involves helping Mother sell cabbages at market, and me overcharging an old villager one jiao – intentionally or not, I can’t recall – before heading off to school. When I came home that afternoon, I saw that Mother was crying, something she rarely did. Instead of scolding me, she merely said softly, “Son, you embarrassed your mother today.”

Mother contracted a serious lung disease when I was still in my teens. Hunger, disease, and too much work made things extremely hard on our family. The road ahead looked especially bleak, and I had a bad feeling about the future, worried that Mother might take her own life. Every day, the first thing I did when I walked in the door after a day of hard labor was call out for Mother. Hearing her voice was like giving my heart a new lease on life. But not hearing her threw me into a panic. I’d go looking for her in the side building and in the mill. One day, after searching everywhere and not finding her, I sat down in the yard and cried like a baby. That is how she found me when she walked into the yard carrying a bundle of firewood on her back. She was very unhappy with me, but I could not tell her what I was afraid of. She knew anyway. “Son,” she said, “don’t worry, there may be no joy in my life, but I won’t leave you till the God of the Underworld calls me.”

I was born ugly. Villagers often laughed in my face, and school bullies sometimes beat me up because of it. I’d run home crying, where my mother would say, “You’re not ugly, Son. You’ve got a nose and two eyes, and there’s nothing wrong with your arms and legs, so how could you be ugly? If you have a good heart and always do the right thing, what is considered ugly becomes beautiful.” Later on, when I moved to the city, there were educated people who laughed at me behind my back, some even to my face; but when I recalled what Mother had said, I just calmly offered my apologies.

My illiterate mother held people who could read in high regard. We were so poor we often did not know where our next meal was coming from, yet she never denied my request to buy a book or something to write with. By nature hard working, she had no use for lazy children, yet I could skip my chores as long as I had my nose in a book.

A storyteller once came to the marketplace, and I sneaked off to listen to him. She was unhappy with me for forgetting my chores. But that night, while she was stitching padded clothes for us under the weak light of a kerosene lamp, I couldn’t keep from retelling stories I’d heard that day. She listened impatiently at first, since in her eyes professional storytellers were smooth-talking men in a dubious profession. Nothing good ever came out of their mouths. But slowly she was dragged into my retold stories, and from that day on, she never gave me chores on market day, unspoken permission to go to the marketplace and listen to new stories. As repayment for Mother’s kindness and a way to demonstrate my memory, I’d retell the stories for her in vivid detail.

It did not take long to find retelling someone else’s stories unsatisfying, so I began embellishing my narration. I’d say things I knew would please Mother, even changed the ending once in a while. And she wasn’t the only member of my audience, which later included my older sisters, my aunts, even my maternal grandmother. Sometimes, after my mother had listened to one of my stories, she’d ask in a care-laden voice, almost as if to herself: “What will you be like when you grow up, son? Might you wind up prattling for a living one day?”

I knew why she was worried. Talkative kids are not well thought of in our village, for they can bring trouble to themselves and to their families. There is a bit of a young me in the talkative boy who falls afoul of villagers in my story “Bulls.” Mother habitually cautioned me not to talk so much, wanting me to be a taciturn, smooth and steady youngster. Instead I was possessed of a dangerous combination – remarkable speaking skills and the powerful desire that went with them. My ability to tell stories brought her joy, but that created a dilemma for her.

A popular saying goes “It is easier to change the course of a river than a person’s nature.” Despite my parents’ tireless guidance, my natural desire to talk never went away, and that is what makes my name – Mo Yan, or “don’t speak” – an ironic expression of self-mockery.

After dropping out of elementary school, I was too small for heavy labor, so I became a cattle- and sheep-herder on a nearby grassy riverbank. The sight of my former schoolmates playing in the schoolyard when I drove my animals past the gate always saddened me and made me aware of how tough it is for anyone – even a child – to leave the group.

I turned the animals loose on the riverbank to graze beneath a sky as blue as the ocean and grass-carpeted land as far as the eye could see – not another person in sight, no human sounds, nothing but bird calls above me. I was all by myself and terribly lonely; my heart felt empty. Sometimes I lay in the grass and watched clouds float lazily by, which gave rise to all sorts of fanciful images. That part of the country is known for its tales of foxes in the form of beautiful young women, and I would fantasize a fox-turned-beautiful girl coming to tend animals with me. She never did come. Once, however, a fiery red fox bounded out of the brush in front of me, scaring my legs right out from under me. I was still sitting there trembling long after the fox had vanished. Sometimes I’d crouch down beside the cows and gaze into their deep blue eyes, eyes that captured my reflection. At times I’d have a dialogue with birds in the sky, mimicking their cries, while at other times I’d divulge my hopes and desires to a tree. But the birds ignored me, and so did the trees. Years later, after I’d become a novelist, I wrote some of those fantasies into my novels and stories. People frequently bombard me with compliments on my vivid imagination, and lovers of literature often ask me to divulge my secret to developing a rich imagination. My only response is a wan smile.

Our Taoist master Laozi said it best: “Fortune depends on misfortune.

Misfortune is hidden in fortune.” I left school as a child, often went hungry, was constantly lonely, and had no books to read. But for those reasons, like the writer of a previous generation, Shen Congwen, I had an early start on reading the great book of life. My experience of going to the marketplace to listen to a storyteller was but one page of that book.

After leaving school, I was thrown uncomfortably into the world of adults, where I embarked on the long journey of learning through listening. Two hundred years ago, one of the great storytellers of all time – Pu Songling – lived near where I grew up, and where many people, me included, carried on the tradition he had perfected. Wherever I happened to be – working the fields with the collective, in production team cowsheds or stables, on my grandparents’ heatedkang, even on oxcarts bouncing and swaying down the road, my ears filled with tales of the supernatural, historical romances, and strange and captivating stories, all tied to the natural environment and clan histories, and all of which created a powerful reality in my mind.

Even in my wildest dreams, I could not have envisioned a day when all this would be the stuff of my own fiction, for I was just a boy who loved stories, who was infatuated with the tales people around me were telling. Back then I was, without a doubt, a theist, believing that all living creatures were endowed with souls. I’d stop and pay my respects to a towering old tree; if I saw a bird, I was sure it could become human any time it wanted; and I suspected every stranger I met of being a transformed beast. At night, terrible fears accompanied me on my way home after my work points were tallied, so I’d sing at the top of my lungs as I ran to build up a bit of courage. My voice, which was changing at the time, produced scratchy, squeaky songs that grated on the ears of any villager who heard me.

I spent my first twenty-one years in that village, never traveling farther from home than to Qingdao, by train, where I nearly got lost amid the giant stacks of wood in a lumber mill. When my mother asked me what I’d seen in Qingdao, I reported sadly that all I’d seen were stacks of lumber. But that trip to Qingdao planted in me a powerful desire to leave my village and see the world.

In February 1976 I was recruited into the army and walked out of the Northeast Gaomi Township village I both loved and hated, entering a critical phase of my life, carrying in my backpack the four-volume Brief History of China my mother had bought by selling her wedding jewelry. Thus began the most important period of my life. I must admit that were it not for the thirty-odd years of tremendous development and progress in Chinese society, and the subsequent national reform and opening of her doors to the outside, I would not be a writer today.

In the midst of mind-numbing military life, I welcomed the ideological emancipation and literary fervor of the nineteen-eighties, and evolved from a boy who listened to stories and passed them on by word of mouth into someone who experimented with writing them down. It was a rocky road at first, a time when I had not yet discovered how rich a source of literary material my two decades of village life could be. I thought that literature was all about good people doing good things, stories of heroic deeds and model citizens, so that the few pieces of mine that were published had little literary value.

In the fall of 1984 I was accepted into the Literature Department of the PLA Art Academy, where, under the guidance of my revered mentor, the renowned writer Xu Huaizhong, I wrote a series of stories and novellas, including: “Autumn Floods,” “Dry River,” “The Transparent Carrot,” and “Red Sorghum.” Northeast Gaomi Township made its first appearance in “Autumn Floods,” and from that moment on, like a wandering peasant who finds his own piece of land, this literary vagabond found a place he could call his own. I must say that in the course of creating my literary domain, Northeast Gaomi Township, I was greatly inspired by the American novelist William Faulkner and the Columbian Gabriel García Márquez. I had not read either of them extensively, but was encouraged by the bold, unrestrained way they created new territory in writing, and learned from them that a writer must have a place that belongs to him alone. Humility and compromise are ideal in one’s daily life, but in literary creation, supreme self-confidence and the need to follow one’s own instincts are essential. For two years I followed in the footsteps of these two masters before realizing that I had to escape their influence; this is how I characterized that decision in an essay: They were a pair of blazing furnaces, I was a block of ice. If I got too close to them, I would dissolve into a cloud of steam. In my understanding, one writer influences another when they enjoy a profound spiritual kinship, what is often referred to as “hearts beating in unison.” That explains why, though I had read little of their work, a few pages were sufficient for me to comprehend what they were doing and how they were doing it, which led to my understanding of what I should do and how I should do it.

What I should do was simplicity itself: Write my own stories in my own way. My way was that of the marketplace storyteller, with which I was so familiar, the way my grandfather and my grandmother and other village old-timers told stories. In all candor, I never gave a thought to audience when I was telling my stories; perhaps my audience was made up of people like my mother, and perhaps it was only me. The early stories were narrations of my personal experience: the boy who received a whipping in “Dry River,” for instance, or the boy who never spoke in “The Transparent Carrot.” I had actually done something bad enough to receive a whipping from my father, and I had actually worked the bellows for a blacksmith on a bridge site. Naturally, personal experience cannot be turned into fiction exactly as it happened, no matter how unique that might be. Fiction has to be fictional, has to be imaginative. To many of my friends, “The Transparent Carrot” is my very best story; I have no opinion one way or the other. What I can say is, “The Transparent Carrot” is more symbolic and more profoundly meaningful than any other story I’ve written. That dark-skinned boy with the superhuman ability to suffer and a superhuman degree of sensitivity represents the soul of my entire fictional output. Not one of all the fictional characters I’ve created since then is as close to my soul as he is. Or put a different way, among all the characters a writer creates, there is always one that stands above all the others. For me, that laconic boy is the one. Though he says nothing, he leads the way for all the others, in all their variety, performing freely on the Northeast Gaomi Township stage.

A person can experience only so much, and once you have exhausted your own stories, you must tell the stories of others. And so, out of the depths of my memories, like conscripted soldiers, rose stories of family members, of fellow villagers, and of long-dead ancestors I learned of from the mouths of old-timers. They waited expectantly for me to tell their stories. My grandfather and grandmother, my father and mother, my brothers and sisters, my aunts and uncles, my wife and my daughter have all appeared in my stories. Even unrelated residents of Northeast Gaomi Township have made cameo appearances. Of course they have undergone literary modification to transform them into larger-than-life fictional characters.

An aunt of mine is the central character of my latest novel, Frogs. The announcement of the Nobel Prize sent journalists swarming to her home with interview requests. At first, she was patiently accommodating, but she soon had to escape their attentions by fleeing to her son’s home in the provincial capital. I don’t deny that she was my model in writing Frogs, but the differences between her and the fictional aunt are extensive. The fictional aunt is arrogant and domineering, in places virtually thuggish, while my real aunt is kind and gentle, the classic caring wife and loving mother. My real aunt’s golden years have been happy and fulfilling; her fictional counterpart suffers insomnia in her late years as a result of spiritual torment, and walks the nights like a specter, wearing a dark robe. I am grateful to my real aunt for not being angry with me for how I changed her in the novel. I also greatly respect her wisdom in comprehending the complex relationship between fictional characters and real people.

After my mother died, in the midst of almost crippling grief, I decided to write a novel for her.Big Breasts and Wide Hips is that novel. Once my plan took shape, I was burning with such emotion that I completed a draft of half a million words in only eighty-three days.

In Big Breasts and Wide Hips I shamelessly used material associated with my mother’s actual experience, but the fictional mother’s emotional state is either a total fabrication or a composite of many of Northeast Gaomi Township’s mothers. Though I wrote “To the spirit of my mother” on the dedication page, the novel was really written for all mothers everywhere, evidence, perhaps, of my overweening ambition, in much the same way as I hope to make tiny Northeast Gaomi Township a microcosm of China, even of the whole world.

The process of creation is unique to every writer. Each of my novels differs from the others in terms of plot and guiding inspiration. Some, such as “The Transparent Carrot,” were born in dreams, while others, like The Garlic Ballads have their origin in actual events. Whether the source of a work is a dream or real life, only if it is integrated with individual experience can it be imbued with individuality, be populated with typical characters molded by lively detail, employ richly evocative language, and boast a well crafted structure. Here I must point out that in The Garlic Ballads I introduced a real-life storyteller and singer in one of the novel’s most important roles. I wish I hadn’t used his real name, though his words and actions were made up. This is a recurring phenomenon with me. I’ll start out using characters’ real names in order to achieve a sense of intimacy, and after the work is finished, it will seem too late to change those names. This has led to people who see their names in my novels going to my father to vent their displeasure. He always apologizes in my place, but then urges them not to take such things so seriously. He’ll say: “The first sentence in Red Sorghum, ‘My father, a bandit’s offspring,’ didn’t upset me, so why should you be unhappy?”

My greatest challenges come with writing novels that deal with social realities, such as The Garlic Ballads, not because I’m afraid of being openly critical of the darker aspects of society, but because heated emotions and anger allow politics to suppress literature and transform a novel into reportage of a social event. As a member of society, a novelist is entitled to his own stance and viewpoint; but when he is writing he must take a humanistic stance, and write accordingly. Only then can literature not just originate in events, but transcend them, not just show concern for politics but be greater than politics.

Possibly because I’ve lived so much of my life in difficult circumstances, I think I have a more profound understanding of life. I know what real courage is, and I understand true compassion. I know that nebulous terrain exists in the hearts and minds of every person, terrain that cannot be adequately characterized in simple terms of right and wrong or good and bad, and this vast territory is where a writer gives free rein to his talent. So long as the work correctly and vividly describes this nebulous, massively contradictory terrain, it will inevitably transcend politics and be endowed with literary excellence.

Prattling on and on about my own work must be annoying, but my life and works are inextricably linked, so if I don’t talk about my work, I don’t know what else to say. I hope you are in a forgiving mood.

I was a modern-day storyteller who hid in the background of his early work; but with the novelSandalwood Death I jumped out of the shadows. My early work can be characterized as a series of soliloquies, with no reader in mind; starting with this novel, however, I visualized myself standing in a public square spiritedly telling my story to a crowd of listeners. This tradition is a worldwide phenomenon in fiction, but is especially so in China. At one time, I was a diligent student of Western modernist fiction, and I experimented with all sorts of narrative styles. But in the end I came back to my traditions. To be sure, this return was not without its modifications.Sandalwood Death and the novels that followed are inheritors of the Chinese classical novel tradition but enhanced by Western literary techniques. What is known as innovative fiction is, for the most part, a result of this mixture, which is not limited to domestic traditions with foreign techniques, but can include mixing fiction with art from other realms. Sandalwood Death, for instance, mixes fiction with local opera, while some of my early work was partly nurtured by fine art, music, even acrobatics.

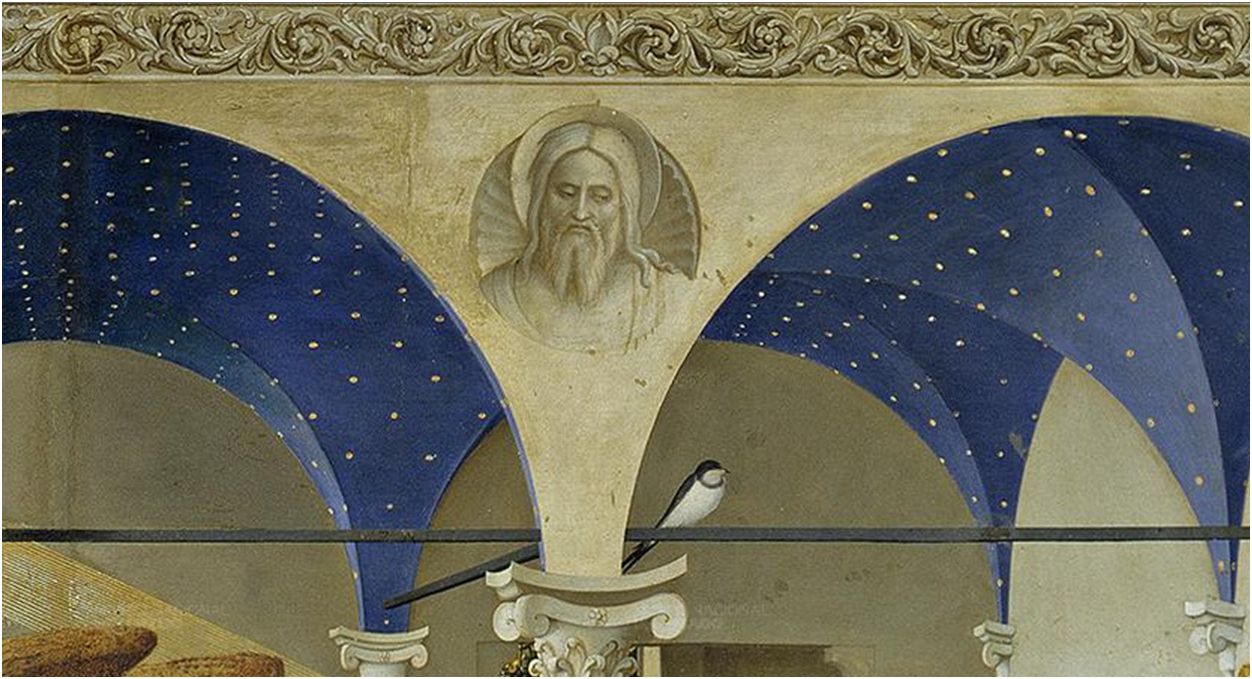

Finally, I ask your indulgence to talk about my novel Life and Death Are Wearing Me Out. The Chinese title comes from Buddhist scripture, and I’ve been told that my translators have had fits trying to render it into their languages. I am not especially well versed in Buddhist scripture and have but a superficial understanding of the religion. I chose this title because I believe that the basic tenets of the Buddhist faith represent universal knowledge, and that mankind’s many disputes are utterly without meaning in the Buddhist realm. In that lofty view of the universe, the world of man is to be pitied. My novel is not a religious tract; in it I wrote of man’s fate and human emotions, of man’s limitations and human generosity, and of people’s search for happiness and the lengths to which they will go, the sacrifices they will make, to uphold their beliefs. Lan Lian, a character who takes a stand against contemporary trends, is, in my view, a true hero. A peasant in a neighboring village was the model for this character. As a youngster I often saw him pass by our door pushing a creaky, wooden-wheeled cart, with a lame donkey up front, led by his bound-foot wife. Given the collective nature of society back then, this strange labor group presented a bizarre sight that kept them out of step with the times. In the eyes of us children, they were clowns marching against historical trends, provoking in us such indignation that we threw stones at them as they passed us on the street. Years later, after I had begun writing, that peasant and the tableau he presented floated into my mind, and I knew that one day I would write a novel about him, that sooner or later I would tell his story to the world. But it wasn’t until the year 2005, when I viewed the Buddhist mural “The Six Stages of Samsara” on a temple wall that I knew exactly how to go about telling his story.

The announcement of my Nobel Prize has led to controversy. At first I thought I was the target of the disputes, but over time I’ve come to realize that the real target was a person who had nothing to do with me. Like someone watching a play in a theater, I observed the performances around me. I saw the winner of the prize both garlanded with flowers and besieged by stone-throwers and mudslingers. I was afraid he would succumb to the assault, but he emerged from the garlands of flowers and the stones, a smile on his face; he wiped away mud and grime, stood calmly off to the side, and said to the crowd:

For a writer, the best way to speak is by writing. You will find everything I need to say in my works. Speech is carried off by the wind; the written word can never be obliterated. I would like you to find the patience to read my books. I cannot force you to do that, and even if you do, I do not expect your opinion of me to change. No writer has yet appeared, anywhere in the world, who is liked by all his readers; that is especially true during times like these.

Even though I would prefer to say nothing, since it is something I must do on this occasion, let me just say this:

I am a storyteller, so I am going to tell you some stories.

When I was a third-grade student in the 1960s, my school organized a field trip to an exhibit of suffering, where, under the direction of our teacher, we cried bitter tears. I let my tears stay on my cheeks for the benefit of our teacher, and watched as some of my classmates spat in their hands and rubbed it on their faces as pretend tears. I saw one student among all those wailing children – some real, some phony – whose face was dry and who remained silent without covering his face with his hands. He just looked at us, eyes wide open in an expression of surprise or confusion. After the visit I reported him to the teacher, and he was given a disciplinary warning. Years later, when I expressed my remorse over informing on the boy, the teacher said that at least ten students had done what I did. The boy himself had died a decade or more earlier, and my conscience was deeply troubled when I thought of him. But I learned something important from this incident, and that is: When everyone around you is crying, you deserve to be allowed not to cry, and when the tears are all for show, your right not to cry is greater still.

Here is another story: More than thirty years ago, when I was in the army, I was in my office reading one evening when an elderly officer opened the door and came in. He glanced down at the seat in front of me and muttered, “Hm, where is everyone?” I stood up and said in a loud voice, “Are you saying I’m no one?” The old fellow’s ears turned red from embarrassment, and he walked out. For a long time after that I was proud about what I consider a gutsy performance. Years later, that pride turned to intense qualms of conscience.

Bear with me, please, for one last story, one my grandfather told me many years ago: A group of eight out-of-town bricklayers took refuge from a storm in a rundown temple. Thunder rumbled outside, sending fireballs their way. They even heard what sounded like dragon shrieks. The men were terrified, their faces ashen. “Among the eight of us,” one of them said, “is someone who must have offended the heavens with a terrible deed. The guilty person ought to volunteer to step outside to accept his punishment and spare the innocent from suffering. Naturally, there were no volunteers. So one of the others came up with a proposal: Since no one is willing to go outside, let’s all fling our straw hats toward the door. Whoever’s hat flies out through the temple door is the guilty party, and we’ll ask him to go out and accept his punishment.” So they flung their hats toward the door. Seven hats were blown back inside; one went out the door. They pressured the eighth man to go out and accept his punishment, and when he balked, they picked him up and flung him out the door. I’ll bet you all know how the story ends: They had no sooner flung him out the door than the temple collapsed around them.

I am a storyteller.

Telling stories earned me the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Many interesting things have happened to me in the wake of winning the prize, and they have convinced me that truth and justice are alive and well.

So I will continue telling my stories in the days to come.

Thank you all.

Translated by Howard Goldblatt