Tags

art, birding, birds, birdwatching, grief, Martin Shaw, nature, painting, philosophy, poetry, Smokehole, Summer Lee, Summer Mei Ling Lee, wild, Wilderness, writing

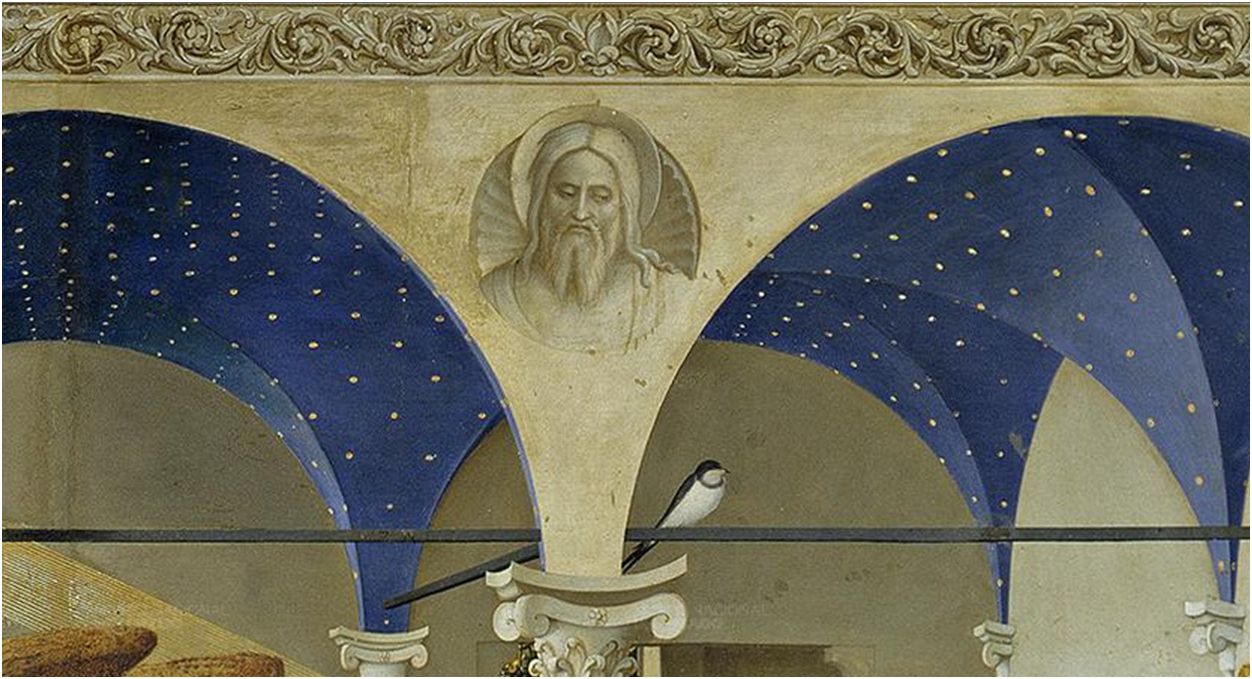

Because the vagrant snow bunting had appeared in my yard before waking, I knew when she called that he was dead. And upon hearing her voice, I began sounding like a strange bird, just uttering no, no, no. As if songs can magically push out reality and hold back time for just a moment.

What’s hard about this one is that he was inside that cathedral with me for many years, and I can still see him running back for me when the most rarest or most gorgeous bird was ahead and I hadn’t caught up yet. And of course, how he told my sons the exact trees where the chickadees were waiting so they could feed them from their hands. How I would wake up and say let’s drive out hours into the prairie to see this lifer and he would always beat me there. And now without warning except for the apparition of a snow bunting we had seen one windy day together two years ago, the cathedral is more empty. With that disappearance, my ancient rituals — timed with spring and fall migrations to welcome the beings from thousands of miles away as they pass through — have fallen into obsolescence.

And here is the ritual of writing, which lately (I apologize) tends to be predictably filling out absences with words. Because he told me, nothing can better bring back a presence than by just the uttering of it.

Nathan sent me some words about the stories we need in our lives and are less and less being told. And in those time-tested tales there is always a moment when we are thrown into the belly of the whale or into the dark woods or what have you. The writer says we are most cautious now of that wilderness, even having chopped off our hands to stop touching what is alive, and asks us to go sit willingly in the wild places and listen to what speaks to us.

I am using words here to listen, deep in another wilderness, sent here by the loss of a soul that scaffolded me, who saw hundreds of birds by my side as I looked at them too. Who sent me birds in every form, and delighted in my birds. And tried as he could to birdwatch in these stupid writings here. I have nothing to offer here because I am still in the wilderness listening, covered in mud, bruised in the middle of me, and seeing ghostly figures in the distance, those who I miss. They somehow feel nearer and nearer to me as I approach my own disappearance.

And yet, by some grace, so much gratitude, there is thanks for those who are waiting in the nearby village, full of love and mercy and words and bird feathers for me. Coming back to tell me they also can hear a beautiful bird just ahead, and they will help me find it.

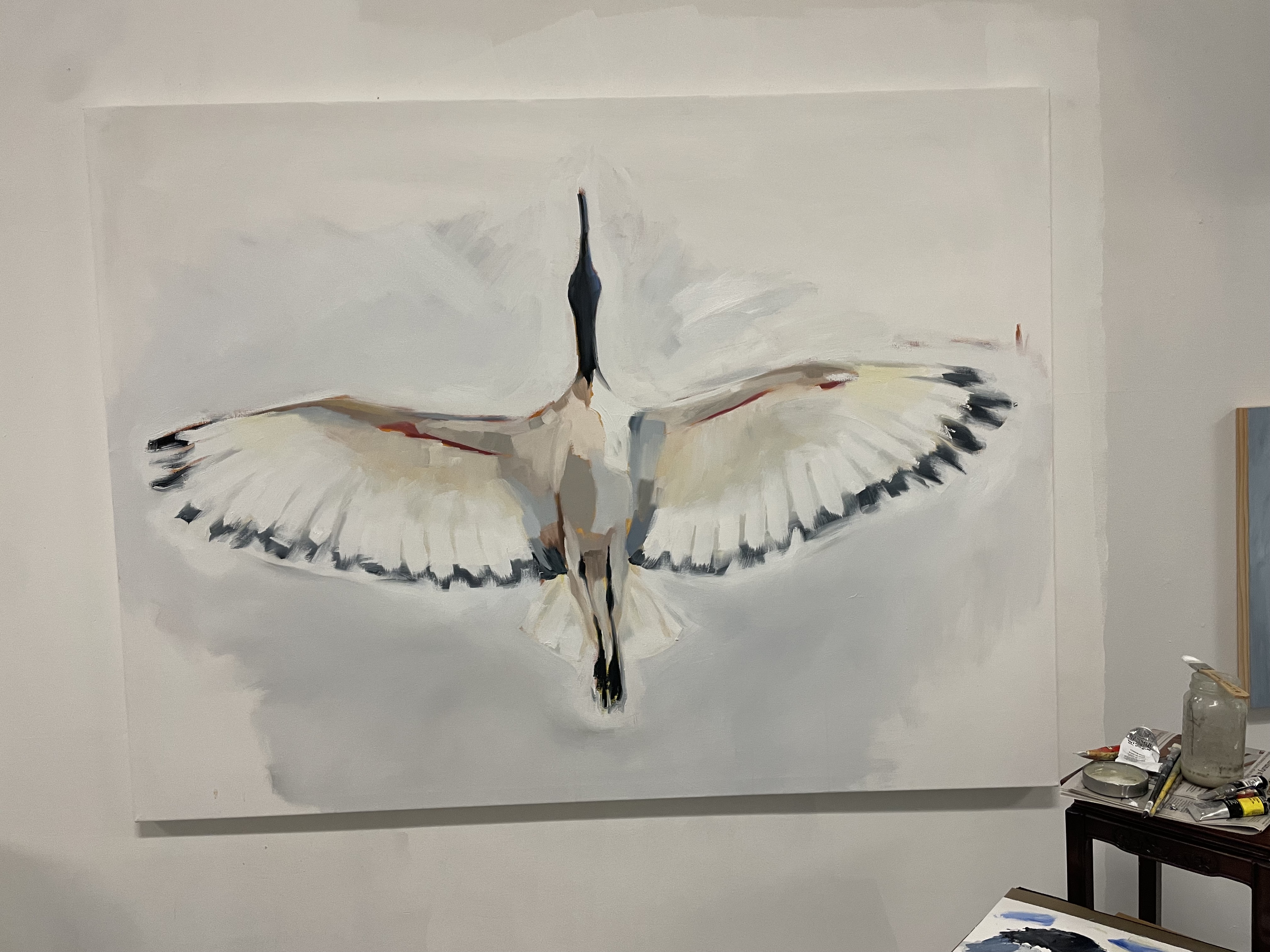

(Annunciation, 2024 by Summer Mei Ling Lee. 23.5 k gold, watercolor and oil paint on wood panels.)

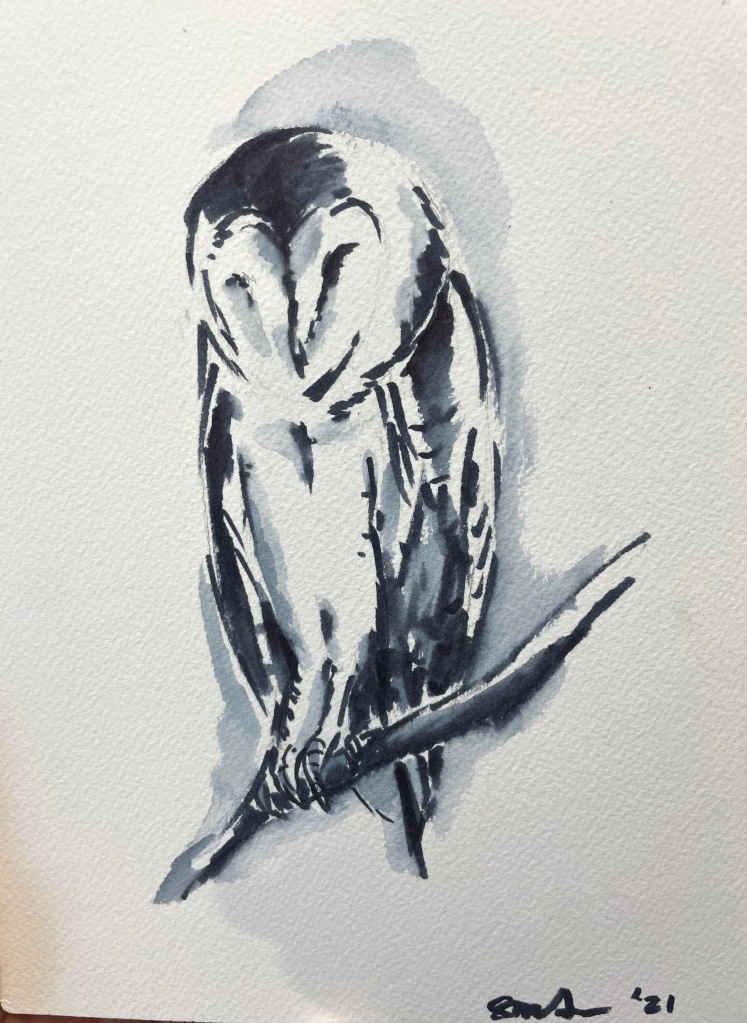

“To be wedded to the wild means some part of you — maybe a large part — guards your solitude like we guard an endangered owl, tells stories as much for the benefit of the lively dead as the moribund living, makes wayward choices many view eccentric, is capable of sustained generosity, has flashed your teeth and counted costs, has dragged meat back to the cave under the moonlight, has stalked all of Russia with only a line of Anna Akhmatova for company. To be wedded to the wild means you have curated a doorway beyond societal expectation of the perpetual, grinding tic of acting nice. That you have recognized discipline as the essential companion of the wildness, that sobriety and ecstasy have made a pact.

That is how good art gets made.” Martin Shaw, Smokehole